Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

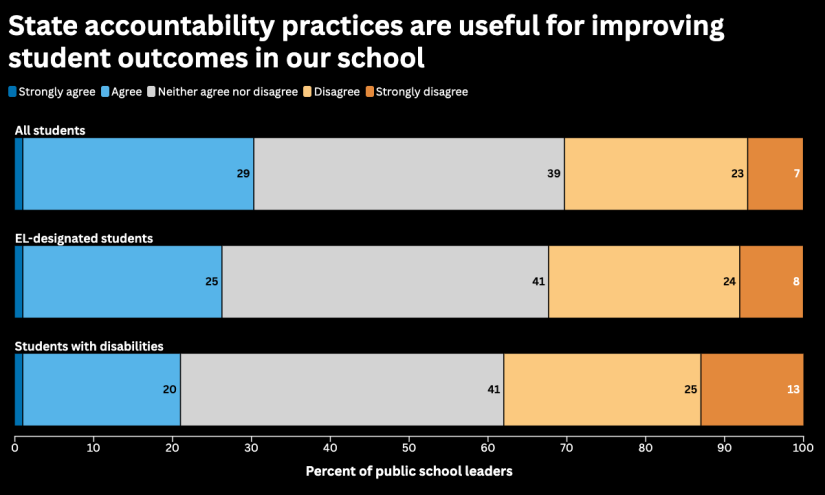

State accountability systems were designed with good intentions: to ensure rigor and drive continuous student improvement. In the latest survey from The Canopy Project, a nationwide scan of nearly 200 leaders from some of the most innovative schools across the country, leaders sent a clear message that current accountability systems are falling short. Only 29% of leaders said accountability data helps them improve student outcomes, and half reported that accountability makes it harder to pilot new approaches and personalize learning.

This low vote of confidence on current accountability systems comes at a time when schools and districts face profound challenges. Artificial intelligence is rapidly reshaping the world of work and social connection. Basic literacy and math skills have been sliding for more than a decade. Families increasingly see schools as out of step with the needs and aspirations of their children. Reimagining school to meet these demands means reimagining the systems of assessment and accountability that surround them.

For the first time in decades state and federal leaders are showing unprecedented openness to rethinking assessment and accountability. This shift offers both promise and peril, especially for new models of learning: Choosing systems with outdated metrics can smother innovation before it takes root, while too little accountability can leave students without clear standards or comparability across schools.

Some argue the answer is to double down — strengthen accountability and demand more tests. Others increasingly question whether holding schools accountable for test scores makes sense at all. But the Canopy survey reveals that school leaders want neither extreme. Only 10% of Canopy leaders favored eliminating accountability altogether, but just 5% supported maintaining the status quo.

Leaders are eager for reform, the Canopy survey revealed. But they also warn that one of the most popular reforms under discussion—through-year testing—may be moving in exactly the wrong direction.

Among these leaders’ critiques of existing systems is a familiar charge — that they rarely provide useful data for improvement. Fewer than one in three leaders said accountability data helps them adjust instruction in meaningful ways. Even fewer found it useful for supporting English learners or students with disabilities. In practice, the data often arrives too late, reflects too narrow a slice of student learning or simply confirms what educators already know from their own local measures.

To address these shortcomings, many states are betting on through-year testing. Instead of a single end-of-year exam, these states administer multiple shorter assessments throughout the year, with the goal of producing timelier and more actionable data. Montana has rolled out a statewide through-year system; Texas passed legislation this fall to replace its annual testing with assessments three times a year; Missouri recently secured federal approval to pilot one under the Innovative Assessment Demonstration Authority; and several other states have either adopted similar plans or are in the process of considering them.

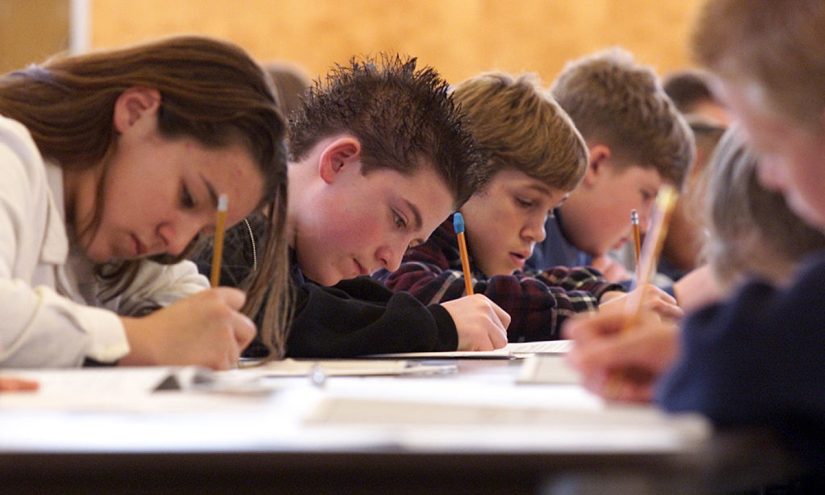

Yet Canopy leaders surveyed are skeptical. When asked to rank possible reforms, they overwhelmingly preferred less testing, not more — by nearly three to one. Their reasons are straightforward. While students may only be tested for several hours, the work required from adults for paperwork, preparation, and proctoring can be overwhelming. Several leaders also stressed that reducing state testing would free up space for richer, performance-based assessments — like public exhibitions, debates, or mock trials — that give students authentic opportunities to demonstrate mastery and teachers find much more instructionally useful.

The case for through-year testing rests on shaky assumptions: that state assessments are inherently more trustworthy than other measures, that they provide unique value beyond what teachers already collect, and that the logistical headaches are worth the benefits. The Canopy Project survey and interviews suggest otherwise. For many Canopy school leaders, through-year testing feels like a well-meaning but misguided boss who requires you to submit a new weekly report “to make your job easier.” Adding new state-mandated tests risks increasing the administrative burden on schools to generate additional data that educators do not want and will not use.

Despite their critiques, school leaders aren’t calling for accountability to disappear. On the contrary, only 10% of Canopy leaders favored eliminating accountability altogether. But even fewer support maintaining the status quo. They voiced strong support for systems that uphold equity and transparency while evolving in three key ways:

First, states should focus on right-sizing the assessment footprint. Don’t ditch testing, but be realistic that no single test can effectively serve multiple purposes. State-mandated tests should be designed to be useful for policymakers, researchers, and other state-level actors, not individual schools or teachers. Accordingly, states should explore shortened tests or alternate-year testing that provide necessary information for state actors while minimizing the administrative burden on schools.

Second, states should differentiate accountability requirements — without lowering standards — for different kinds of schools. Leaders of specialized schools told us that accountability systems ignored progress on indicators that are core to their missions, like providing industry-accepted credentials or reengaging students after extended absences from formal schooling. In Washington, D.C., the Public Charter School Board has launched a new accountability framework that provides room for “school-specific indicators,” mutually agreed upon by schools and the authorizer; states could consider a similar approach.

Finally, states have the opportunity to incorporate a broader set of measures into accountability systems, such as those related to learning opportunities and student engagement. States like Illinois already include school climate measures in their accountability systems, and Canopy leaders are interested in scaling up their use while exploring ways to avoid misplaced incentives.

Accountability systems need reform, but simply doubling down on existing models by layering on through-year tests is not the answer. Instead, new learning models require new forms of accountability so that today’s guardrails don’t become tomorrow’s handcuffs.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how